Blog

A typical hackathon sight - people on the computers. Markel can be seen on the right, in a grey jumper.

It was different in a good way - the 2024 nextGEMS+WarmWorld+EERIE Hamburg Hackathon was better than what I had seen before. A very good thing about these projects, such as EERIE, is that they’re open science driven, which makes the life of data-viewer makers a lot easier as colleagues publish data openly and we can monitor what they’re doing.

There were differences between the simulations of the different projects, such as the format and location of the data. However they were easy to access thanks to the Intake catalogues prepared by the technical support team. Technically, the preparation of the hackathon was flawless and this makes all the difference when it comes to being productive. It was great to see the participants talking about science right from the very beginning instead of struggling with technical issues.

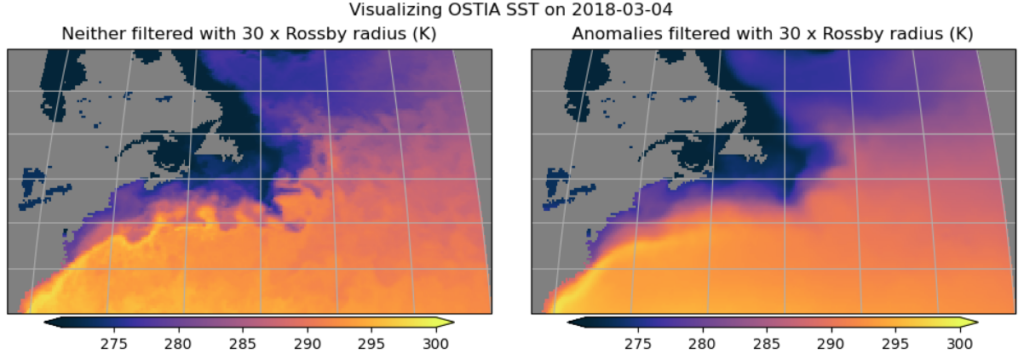

There were several groups sorted not by challenges as I had seen before but rather by topic. The groups were highly dynamic with continuous discussions, instead of participants working on their own. The group I took part in was called Whirls of Wonder and we were working with an eddy-tracking software. In my case, I was checking how climatologies differ between the different AMIP simulations (simulations where the sea surface temperature is prescribed from observations) runs. In some of these runs the eddies were removed in different ways using spatial filters (see the figure below). I continued with a jupyter notebook our former colleague Iuliia Polkova had started during the 2023 EERIE Bremerhaven Hackathon and I could use it thanks to the project’s open data approach. I worked on monthly data to try to speed things up, but I also opened the six-hourly ones for testing the performance, which was great.

Figure 1: Observed Sea surface temperature (SST) from the OSTIA dataset on 2018-03-04 over the Northeast Pacific. This SST was prescribed in the AMIP simulations. The left figure shows the original data, while in the right the eddies have been removed by using an spatial filter. The goal is to see the direct effect of the eddies by running the same model with both SSTs and comparing them (Author: Matthias Aengenheyster).

I made a simple data viewer where the climatologies of the AMIP simulations from EERIE can be directly compared to the filtered one or choose other variables, by season, zooming in and out, colour palettes… It was just a simple notebook version, but I wanted to show how easy it is to visualise data this way instead of ending up with folders with hundreds of png files.

Figure 2: Simple data viewer Markel built in the hackathon for comparing AMIP simulations.

It was an overall fantastic experience and there were some key take-home messages for me, working on the project’s Data Viewer and aspects to be considered: the great interest on event-based studies such as eddies, cyclones, with a set impacts, trajectory and duration, as well as monsoon, clouds and high-frequency precipitation patterns. The AMOC and heat fluxes are capital too, of course. In this phase of the projects there is a lot of interest in visualising and comparing long term averages, instead of climate change “deltas” (average differences between historical and future projections). The focus is now on optimising how the models reproduce the historical (observed) climate and understanding the impact of eddies. Of course this will change in the late phase of the EERIE project when all the data will be available.

Needless to say not everything was perfect, as the venue was a bit overwhelmed by the large number of participants at the beginning. But that was pretty much all the downsides I could see in the event.

And in case you want to see pictures of the Hamburg hackathon, here’s a photo gallery.

8 February 2024

As we mark the International Day of Women and Girls in Science on 11th February, two EERIE Project scientists have shared their experiences and their thoughts on what’s needed to achieve equality in their field - and there’s a long way to go!

Meet Dr Ting-Chen Chen from Taiwan, 34, who studied her PhD in Canada, and Dr Stephy Libera, 28, from India, who pursued her PhD in Australia, both currently researching air-sea ice-ocean interactions at the Université Catholique de Louvain.

Why and how did you get interested in your research field?

Ting-Chen: I got into atmospheric science by chance. In Taiwan, the college admission process generally starts with students taking the university entrance exam. My score was not high enough to be admitted to the “superior majors” (usually the ones that lead to more high-paying job opportunities), and among the possible options, I saw earth/atmospheric sciences. Not until then did I recall the very few hours of earth science courses in high school, and I thought I actually liked it back then, so why not give it a try?. That somewhat random decision turned out to be one of the most important decisions that changed my life completely. After I went to the Department of Atmospheric Sciences at the National Central University, I felt more and more intrigued by the science behind the weather and climate. I was particularly amazed by how we can predict the weather by applying fluid dynamics, thermodynamics and numerical computations. When I had the chance to choose a research topic for my master’s program, I decided to study one of the most impactful weather systems in Taiwan, tropical cyclones.

Stephy: I was doing my bachelor’s in physics, I was not interested in doing an MSc in physics which at the time seemed like learning more theory, and concepts that didn’t seem to have real-world relevance to me. When I heard about oceanography, I was curious and I felt that learning more about the world we live in, understanding its physics and what processes drive it, had implications to the society that I was part of.

Was there anyone who inspired you to pursue that career?

Ting-Chen: It kind of happened naturally. If I must name some names, I would say my mom’s support and understanding that climate science is a crucial issue globally was quite important to me in making the decision. And many great, rigorous and humble scientists I met along the way all played roles in keeping me interested in this field of study.

Stephy: I heard about oceanography in the final year of my bachelor’s degree. It was not a well-known field where I lived, so I had not known anyone in the field. One of my professors who had noticed a pattern in the seminars I gave in college on rare clouds, rare natural phenomena, and similar topics, knew I had an interest in Earth sciences in general and supported me.

Dr Stephy Libera onboard the SA Agulhas during the Indian Southern Ocean Expedition 2017-18.

Do you know women belonging to previous generations working in your field? What did they tell you about their experiences and challenges they had to overcome?

Ting-Chen: Yes, there were some (and getting more in the past few years) female professors in my universities. I cannot recall any gender-specific challenges that they had to overcome, but I do remember vividly that the first few questions they asked me after hearing that I considered studying abroad were “How about your boyfriend”, “Do you plan to have kids”, etc. I’m not saying that they were reinforcing traditional gender expectations on me; Instead, I think those questions and the follow-up advice, such as “If you want to have kids, do it when you’re still in PhD. It’s gonna get harder later” reflected the problems that women tend to struggle more, the timing of pursuing a career and building a family.

One relevant observation that I had during these years living abroad in North America and Europe is that there are many females who gave up their jobs in their countries to follow their husbands to move/study/work abroad, but there were seldom the opposite case.

Stephy: In India, before I joined my master’s program in Physical Oceanography, I didn’t know of female (or male) researchers in the field. However, considering the amount of resistance that I faced from my circles for my decision to take oceanography, I can certainly say, it would not have been easy for many females in the previous generation to enter the field. I was told it is a job for a man, that it is risky to go to the sea and that being a female I wouldn’t be able to succeed in the field. These comments were made by professors in other fields, family, and friends, who like me, also were not aware of what the field of physical oceanography entailed. Yet, because I was a female and the field was something they perceived to be risky, I was very much discouraged from joining. I was stubborn (I am grateful for that), I joined my Master of Science (MSc) degree in physical oceanography at the Cochin University of Science and Technology (CUSAT) and enjoyed learning the subject. In 2018, as a part of my MSc project, I was able to go for field work in the Southern Ocean, which was one of the best experiences in my life, and it anchored me to continue my studies and research in polar oceanography.

During my PhD in Australia, I had a female supervisor in my team. I have seen her set a role model in many instances and I was very grateful to have her guide me in my research journey. We had formal and informal conversations where she shared perspectives on research, work-life balance, career, and the likes, that was vital to keep me on track. I also sought out mentoring from other senior female researchers in the field. These researchers have overcome many hurdles and still face many challenges. I have seen some of them raise moral issues in meetings when some of the senior (male) researchers make negative or discriminative comments or behaviors, when important group meetings become overridden by senior male researchers debating over their points or perspectives, often not giving everyone at the table an equal voice. I have seen these female researchers have tough conversations to be just on the same level field, the extra efforts they need to put to be somewhere they should be. Yet in many instances the female researchers that stand up for themselves and the benefit of others are often considered troublemakers.

What difficulties have you faced throughout your academic and professional career your male colleagues didn’t have to worry about? Have you ever felt discriminated against during your academic and/or professional career?

Ting-Chen: I guess one common worry many of my female colleagues share is that it is more difficult for women to advance through academic ranks if they decide to have children, as maternity leave would create a career gap that is difficult to recover from. This issue particularly concerns early-career scientists who are on limited-term employment contracts. If we need to constantly provide proof of our professional performances (publications) to secure the next contract every one to three years, potentially in a different country, how can we have babies now? I believe this challenges women’s academic careers more than men’s.

While direct sexual discrimination was not common in my experience, I do get sexist comments from time to time. An example happened when I was in an international summer school. All participants were separated into groups randomly to work as a team. When my group members and I were discussing each other’s duties for the team project, one said to me, “You should present the work on the stage since you are the only female in this group.” The other recent incident happened in an invited seminar at a university. After I finished my presentation, one professor in the audience said to me that he was somewhat disappointed, because he expected something different (in terms of research content) and he sighed “Oh well, this is not the first time I got fooled by pretty girls.”

Stephy: So far, I have been fortunate that I have not faced any major discrimination as a female (or that I am aware of). However, there are many instances that my female academic peers and I have encountered happening to people we know or people around us. Some are subtle, some not so much. An example is "being the only woman in a lab". Even if there is no direct discrimination, in many situations there is a sense of "camaraderie" between the men that makes women feel isolated. This applies both personally and scientifically, sometimes great science ideas are discussed over lunch/coffee/beers and if the women are not invited, they will not participate.

Another common issue is females being judged for appearance rather than for science (e.g., comments like "what a pretty girl", and not "what a nice presentation", “oh it’s not just beauty, you’ve got some brains”, etc). Female researchers after becoming mothers are not being asked to join projects because "they seem already too busy".

And unfortunately, we still have a lesser number of females at the senior or permanent positions.

I have also experienced some minor predatory behavior during my field experience, one of the senior researchers that joined the research voyage from a non-oceanographic field was sexist and disrespectful. While the experience of being groped is unfortunately too common in India (in public transport or busy streets), it happening from a senior researcher in your expedition was gross. My experience is way too minor compared to the experiences I have heard from other female researchers in the field. Efforts are still going on to improve the safety and working conditions of women in field work, especially in the polar regions.

Dr. Ting-Chen Chen presented her work on "Climatology of wind and precipitation extremes induced by extratropical cyclones over northeastern North America" at the National Central University, Taiwan, on 17 Jan 2023. The screen showed the famous "Halloween Storm" hitting eastern North America with damaging winds and heavy precipitation, causing insured losses of over CA$250 million in 2019.

How do you think the access to these degrees and careers could be made more accessible to women?

Ting-Chen: Despite what I said above, I still think academia has come a long way toward gender equality. It is true that the field is still dominated by men, especially in higher-level positions, but I have seen more and more female students, great scientists and young professors in recent years. This is an indication that we are on the right track! And there are also some scholarships, funding, or even job opportunities that give priority to women. So, women are not necessarily in an inferior position in terms of degree accessibility in many places nowadays. For countries, regions, or institutions that still have high gender imbalances, taking viable actions to increase the ratio of females is crucial to break the cycle. It is natural that females would feel less encouraged and tend to be held back from pursuing degrees or careers in a male-dominated place.

Stephy: Through awareness, encouragement and support.

Awareness at the grassroot level ― Although it is changing in India, in many communities spending resources on a female for higher education is considered a loss for she is to be married away. If she was to have a job (depending on the decision of her husband and family), the benefits from her job goes to the in-law family and her parents usually don’t get much support. So many families prioritize the education and job prospects of the male child (expected to take care of the aging parents) for the long-term benefit of the family and their financial stability reinforcing the male “breadwinner” and the female “homemaker” roles. Building awareness in these communities, often by challenging its traditional views and presenting educated females in societally relevant roles may promote more young girls to gain higher education.

Encouragement ― Young students (especially females) from underprivileged backgrounds lack knowledge about higher education opportunities like scholarships and career pathways. Importantly, in many occasions they lack confidence to pursue these pathways. It is essential to encourage and inspire these students to pursue higher education. During school and college I believed a career in Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics and Medicine (STEMM), doing scientific research, was something out of reach. I had not seen anyone that I knew of who was a researcher and had never heard about oceanography. This memory inspired me to visit schools and colleges in India and share my experiences about research and career in STEMM often targeting females. I also used to think that I was an average student and research was exclusively for high achieving (in terms of grade) students, and I tell the students that I was only someone that barely managed to pass Physics and Math in high school, and that they can do it too. I believe it is important for more students to see someone relatable in STEMM.

Support ― Although a high proportion of female students and researchers enter at the graduate, postgraduate, PhD, and even postdoc levels, very few female researchers are found in the higher ranks (such as project investigator, chief investigator, professor, and other long-term positions). To improve the representation of female researchers at these higher levels, we need to identify the hurdles that female early career researchers face in taking up leadership roles and equip them with resources and support to progress in their career.

What would you say is still needed in order to achieve gender equality there too - in the higher levels?

Ting-Chen: I think the main challenge for female academics comes at the later stage of their career, to climb up and secure a stable job in a competitive environment while building a family. There’s no easy way to ease this, and it is to some degree connected to a bigger-scale problem in the academic system; for example, there are too few permanent job positions and postdocs are forced to change from one place to another. In practice, improving childbirth support may attract more women to continue the career path<. We should also continuously discuss the sustainability of academia and how to spare the burden of postdocs who need to constantly seek the next job opportunities.

Stephy: I believe improving the retention of women in science, to have more women in leadership roles is one of the goals to achieve, while sustaining efforts at grassroots level to continue inspiring females to science. It’s no use to fill the pipe at the one end without plugging the holes.

What professional goals do you expect to achieve?

Ting-Chen: I enjoy conducting weather/climate-related studies and I take pride in pursuing rigorous research, but right now I don’t have any “ambitious” professional goals set for the future. I’d like to stay open-minded in terms of career, either academia or industry. My practical expectation for the long term is to secure a stable job that allows me to continue doing research or working in weather/climate-relevant fields that I personally feel motivated by.

Stephy: I remember when I completed my MSc degree, I was telling myself that in 10 years, I would like to gain some field and research experience and then get into teaching. Now it is not that clear, yet I consider teaching or science communication to be something I would like to do more in the future. I believe there is value in communicating science to a non-scientific audience. I have always put in effort when it came to communicating concepts (like using an analogy that could help them grasp a concept or use visuals or very simplified models). I enjoyed it when members of the audience engaged in discussions or told me they understood the concept and I always found it rewarding. So, somewhere along the line, I may get into teaching or do science outreach. I joined oceanography also with the dream of doing field work. I am very happy to have had an opportunity, but I will try to get more field work in the future.

20 November 2023

Born in Hamburg but settled down in Bonn after living and studying in several countries, ECMWF’s Matthias Aengenheyster says work and his passion for taking pictures often converge.

“I love biking, hiking and photography – locally or while travelling around. This also relates to science”, he claims. “One part of my work is visualising data to make sense of them. Sometimes this can almost stretch into art, tweaking the visualisation to be both nice to look at and to show the physical features that I am interested in”, the postdoc adds.

Aengenheyster started to work at ECMWF for EERIE after his PhD at UK’s University of Oxford. That was hardly his first time living abroad: “I’ve always liked moving around and meeting people from all over the place – spending a semester in Canada during high school, studying at hyper-international Jacobs University, doing degrees in the Netherlands and the UK, and shorter research stays in a few more countries”.

He says he’s happy to have “settled down a bit in Bonn”, but he’s quick to add – “one great thing about doing science, and in particular at ECMWF and international projects such as EERIE, is interacting with a lot of people – scientifically, personally and culturally. So I’m sitting in my office in Bonn having sweets that a colleague brought from Hungary, while asking someone in Spain about some problem I have with the climate model.”

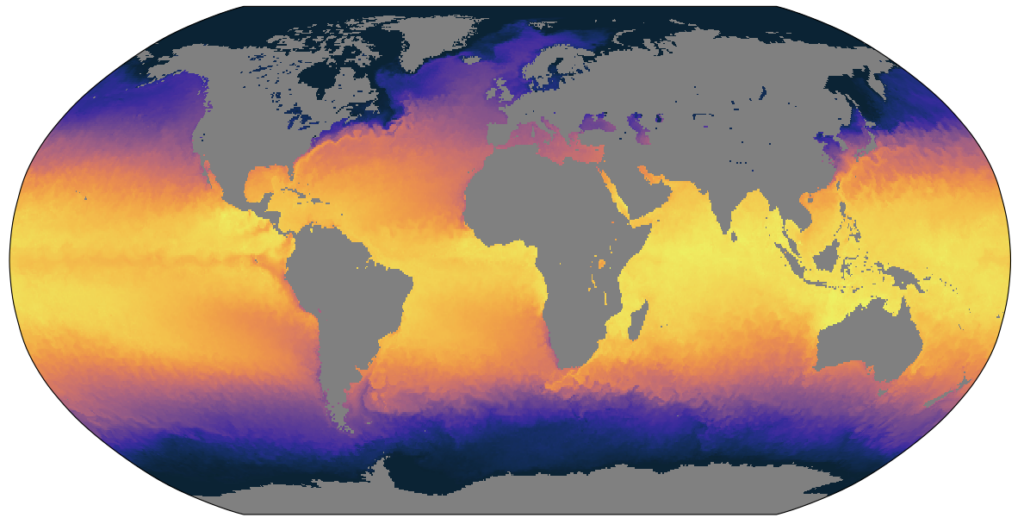

One day of observed sea-surface temperature from the OSTIA dataset at 1/20th degree spatial resolution (around 5 km).

“At the moment my focus is on addressing the various scientific and technical questions required to conduct the long model simulations”, Aengenheyster explains. “This involves choosing the sea surface temperature dataset and other physical input parameters, testing how the model behaves and how fast it runs. I am also involved in a lot of coordination in the project. Several institutions use the ECMWF model Integrated Forecasting System (IFS) as the atmospheric component of their coupled models, and everyone wants to be closely aligned.”

The ECMWF scientist maintains there’s a visible connection between his previous PhD work and his current job for the EERIE project. It lies “on the link provided by air-sea heat fluxes between oceanic and atmospheric dynamics”. He further adds: “Since starting to work on climate physics for my undergraduate thesis, I have worked on a range of scales in space, time and model complexity, from large-eddy simulations to simple climate emulators.”

In the case of EERIE, it’s “intimately concerned with how air-sea interactions impact weather and climate on timescale from subseasonal to multidecadal, spanning a broad range of processes and phenomena. This is scientifically very interesting (which small-scale features in the ocean have large-scale impacts in the atmosphere?) and also important for climate change (what do we need in ocean models and forecasting systems to describe the near-term weather and long-term climate trajectories?)”.

Aengenheyster points out “central to EERIE are the eddy-resolving coupled model integrations over many decades, with the goal of finding out the impact of mesoscale structures that can be resolved in high-resolution ocean models”.

Aengenheyster during the EERIE Hackathon 2023 in Bremerhaven (Germany).

“One way to investigate this”, he says, “is to compare the results of high-resolution simulations with lower-resolution ones. However, the resolution of the ocean model affects many aspects of the ‘ocean state’, and so it is difficult to deduce how much of any difference is directly due to the presence of eddies”.

A way forward for this “is to conduct idealised experiments”. That’s why the ECMWF contribution to EERIE are the so-called AMIP simulations – “We run the atmospheric model without an ocean but directly provide the model with information about the sea surface, most importantly sea surface temperature, which we take from observational datasets. We can also remove mesoscale features from the observed sea surface temperature dataset, and thus compare between model atmospheres that have seen and have not seen mesoscale sea surface temperature variability, while the large scale features are the same”. The goal for this is answering a key question – “What is the impact on the atmosphere of the presence or absence of eddies, while the implied large-scale ocean state stays the same?”

This is not the only question to be answered, the scientist admits – “Running a climate model simulation is one thing, understanding what it does and why is quite another”.

“However this is the crucial bit”, he highlights – “Both to generate scientific insight and knowledge and to make those models and simulations useful for society and policymakers”.

6 July 2023

By Eduardo Moreno-Chamarro and Eneko Martín

At the end of May, members of the EERIE project participated at the Cycle 3 Hackathon organized by the nextGEMS project at the Universidad Complutense in Madrid. NextGEMS is a European-funded project to build prototypes for new storm-resolving earth system models (this is, with extremely fine horizontal grids), which will allow representing the climate system for the next 30 years much more realistically.

The EERIE project participants attending the nextGEMS hackathon in Madrid

For about a week, participants at the Hackathon had the opportunity to analyze the data of the new Cycle 3 simulations from the three climate models contributing to nextGEMS, while interacting with many top scientists from all over the world. The participants, divided into different thematic groups (Atmosphere, Ocean, Land, and Society), engaged into discussions about the advances in a diversity of processes (such as precipitation and cloud distribution, linkages between wind stress and the mixed layer depth over the Southern Ocean, fronts along tropical instability waves, and tropical cyclones) on wide range of scales (from very local, for example just over Paris, to global scales), taking advantage of the extremely high temporal and spatial scale of the simulations. The data, nicely prepared by the modeling centers to facilitate their analysis, encouraged participants to use new and more effective tools, grids, and organization systems. Participants in the Ocean groups, for example, applied an algorithm for ocean eddy tracking that provides the main characteristics of the eddies, including their size, location, and spin direction. All the participants also got the opportunity to interact with the new grid of the ICON model, HEALPix, which is designed to facilitate data analysis. For some others, this Hackathon was their first opportunity to use different analysis tools for the first time (python, for example). The meeting thus served as the perfect platform for the exchange of ideas and fun science. By the end of the meeting, each of the thematic groups presented their findings and discussed the results.

The participants also enjoyed three keynotes lectures, by Prof. Katja Fennel (Dalhousie University), Prof. Francisco Doblas Reyes (Barcelona Supercomputing Center), and Prof. Yukari Takayabu (University of Tokyo), who covered recent efforts in biogeochemistry modeling and observation, user-oriented high-resolution modeling in DestinE, and the observations of heavy precipitation events respectively.

In many aspects, the nextGEMS Hackathon proved to be a very successful story for EERIE. The meeting represented an ideal setting for its members to engage with projects with similar interests in high-resolution modeling, helping bridge future collaborations and synergies. So it was made clear on the last meeting day, when it was highlighted that the experiments planned within EERIE might benefit nextGEMS members to study climate change with a temporal extent longer than it is currently planned in the project. Meeting in Madrid also let EERIE members start to know each other and build the much-needed network that will lead to the project success. Similarly, it also allowed us to gather ideas and plans for the organization of our own hackathon in November 2023.