The Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP) has been pivotal in advancing our understanding of the Earth’s climate, enabling multi-model studies to simulate past, present, and future climate conditions. However, the computational demands of these models also result in energy consumption and carbon footprint. While the benefits of these simulations outweigh their costs, and their environmental impact is modest compared to other industries, it is a challenge for the weather and climate community to understand and quantify the computational cost of this CMIP exercise. For this reason, there has been a growing emphasis on developing standardised computational metrics to measure and optimise the performance and energy efficiency of climate simulations, ultimately reducing their environmental impact.

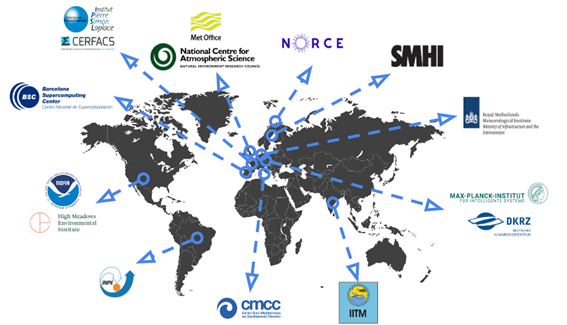

In this context, the ENES-MTHPC-TF has played a critical role in pioneering the collection of computational performance data during CMIP6. By coordinating efforts across institutions (Figure 1) and compiling CPMIP (Computational Performance for Model Intercomparison Projects) metrics from 33 experiments (Acosta et al., 2024). This initiative, supported by IS-ENES3 project and supported by ESiWACE3 nowadays, has provided an unprecedented dataset, serving as a benchmark for performance comparisons and optimisation strategies for new projects such as EERIE, where we are also working to ensure proper throughput of the model simulations while maintaining good computational efficiency and minimal energy cost of the experiments to be done in the supercomputers.

Figure 1. Institutions around Europe contributing to the performance metrics collection.

Importance of Standardised Metrics

The work done underscores the necessity of standardised metrics for evaluating the computational and energy performance of Earth System Models (ESMs). Metrics such as Simulation Years per Day (SYPD), Core Hours per Simulated Year (CHSY), and Coupling Cost have proven invaluable for identifying bottlenecks and inefficiencies. These set of standardised metrics not only quantify energy usage but also reveal areas for optimisation, such as reducing idle times, balancing computational loads, and improving I/O operations.

A critical takeaway is that queue times and system interruptions accounted for up to 78% of execution overhead in some cases. This variability highlights the importance of optimising workflows and ensuring equitable access to HPC resources.

Key Insights on Energy and Carbon Footprint for the previous CMIP6 exercise

The energy consumption and carbon footprint associated with CMIP6 experiments provided some insights and lessons for our present experiments:

- Energy Costs: The experiments analysed used approximately 1,692 tons of CO₂ equivalent for execution, based on the energy demands of high-performance computing (HPC) platforms. These simulations encompassed 14 different HPC machines, each with varying energy efficiencies.

- Metrics for Efficiency:

- The Joules per Simulated Year (JPSY) metric was introduced to quantify the energy efficiency of each simulation. This revealed significant variability across institutions, platforms, and configurations, emphasizing the need for consistent methodologies to report energy consumption.

- Some models were able to achieve notable energy savings through better parallelization and resource management, while others exhibited inefficiencies, particularly in coupling costs and queue times.

- Carbon Footprint Variability:

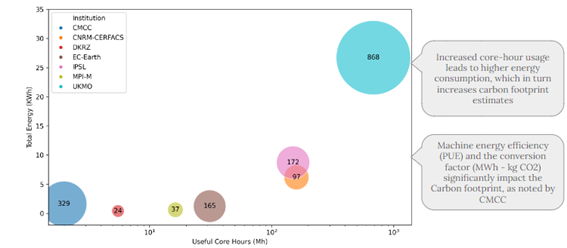

- The carbon footprint of HPC platforms (Figure 2) varied based on factors such as local energy sources and Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE). Institutions relying on renewable energy grids had a substantially lower carbon footprint compared to those using fossil-fuel-intensive grids.

- Models with high resolution or added complexity often required significantly more computational resources, leading to higher emissions. For example, coupling between model components increased computational overheads by 5–15%, which scaled poorly with higher processor counts.

Figure 2. Energy consumed comparison (total energy versus core hours used for CMIP6) among institutions.

Looking Ahead to CMIP7

Building on the lessons from CMIP6, future exercises such as CMIP7 can leverage these insights to further reduce the environmental footprint of climate simulations. The methodologies developed at Barcelona Supercomputing Center (BSC), particularly the comprehensive collection of CPMIP metrics, will be crucial in achieving this goal. Key recommendations include:

- Standardisation Across Institutions: Harmonising the reporting of energy and computational metrics to ensure comparability and transparency.

- Optimising HPC Resource Use: Encouraging the use of energy-efficient platforms and prioritising renewable energy sources to minimise the carbon footprint.

- Enhanced Workflow Management: Developing tools to automate load balancing and minimise idle times, particularly for high-resolution and multi-component simulations.

Pioneering work collecting CPMIP metrics has established a blueprint for these efforts, showcasing the potential for collaborative, data-driven optimisation in climate science. By reducing inefficiencies and adopting sustainable computational practices, the climate modelling community can align its operational goals with the broader climate change mitigation mission.

What about EERIE?

There are different European initiatives to improve the throughput of ESMs that take advantage of the CPMIP metrics, such as the EERIE project. EERIE aims to develop a new generation of ESMs that are capable of explicitly representing a crucially important, yet unexplored regime of the Earth system – the ocean mesoscale, a real challenge from a computational perspective due to the very high computational cost to make it possible. To ensure an efficient exploitation of the computational resources, the goal is to achieve a simulation speed of up to 5 SYPD and to make efficient use of the EuroHPC pre-exascale supercomputers. Different ESMs developed by European institutions are used in EERIE, including HadGEM3 (Met Office), ICON (MPI-M), IFS-FESOM (AWI), IFS-NEMO (BSC) and IFS (ECMWF). These models use different configurations for the ocean component, where the finest resolution for some of them is around 5 km.

All these models are profiled and optimised to maximise the throughput, minimise the energy cost and achieve the set goal by leveraging a wide range of computational optimisations such as reducing the numerical precision of floating-point operations ensuring the scientific accuracy, use of Graphic Processing Units (GPUs) to speed up computationally expensive modules, tuning of the Input/Output (I/O) process to efficiently dump data into the storage system, tuning of the model configuration as well as the infrastructure ecosystem, recommendation of best practices, etc. The new approach in EERIE to tackle the analysis and optimisation of all models is through the offer of HPC services among partners. The services are flexible since they are offered upon request, they allow HPC experts and model developers to discuss and agree on what to profile, and provide a final report including findings and suggestions of optimisations.