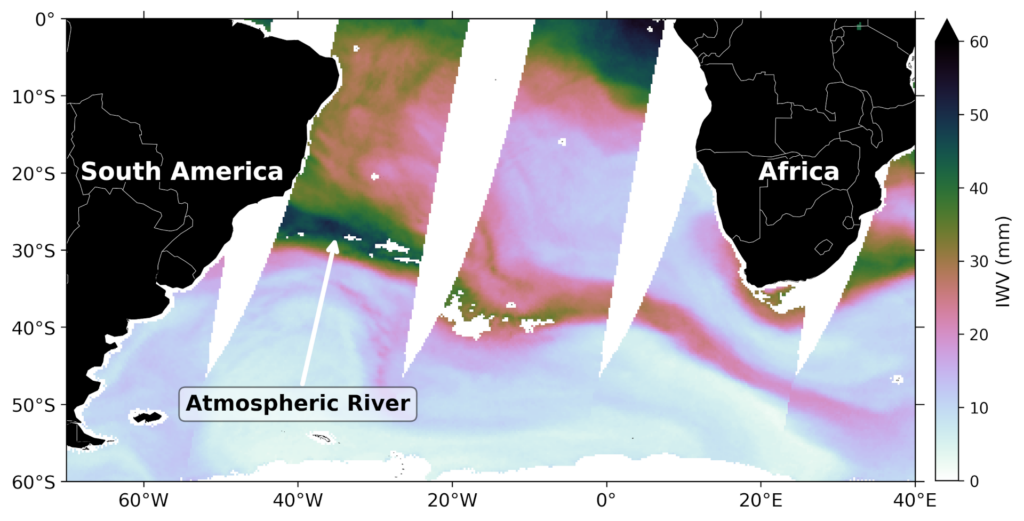

Imagine a river, not on the ground, but rather flowing above us… Yes, above us in the atmosphere. These ‘rivers’ in the sky are what scientists’ term Atmospheric Rivers (ARs). ARs are not rivers in the sense that they are made from liquid water flowing as it does on the ground, but rather concentrated river-like plumes of water vapour in the atmosphere (see Figure 1). They can stretch thousands of kilometres, transporting large quantities of moisture from the tropics to the Midlatitudes.

Contrary to what a non-expert may think, Atmospheric Rivers are not rare features in the Earth's climate system, with anywhere from 4 to 5 present at any given time across the Earth’s Ocean basins. Why these features are so important is because they play a key role in the global hydrological cycle, bringing fresh water to communities and diverse ecosystems across many of the midlatitude regions. On the contrary, they can also contribute to some of the most damaging storms and floods in these regions. A good example of this is the well-studied AR in Northern America, affectionately known as the ‘Pineapple Express’, which supplies California with up to 50% of its annual rainfall. However, the Pineapple Express has also been shown to result in heavy flooding along the West Coast of Northern America.

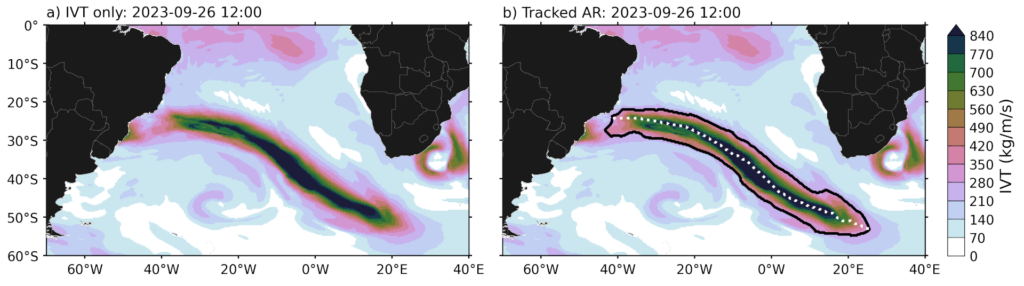

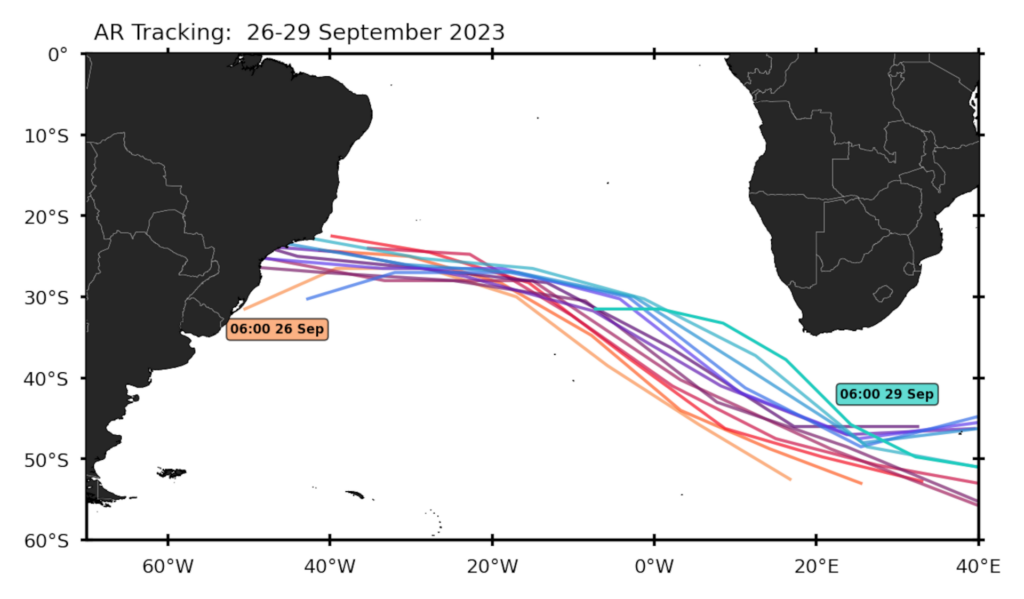

Understanding the frequency, intensity, and behaviour of ARs is not just important in an academic sense – it is crucial for regions such as Southern Africa, which are highly vulnerable to rainfall-related extremes, including both floods and droughts (just think back to the Cape Town ‘Day Zero’ drought from 2015-2018, where around 4 million inhabitants nearly ran out of fresh drinking water). Figure 1 above shows an example of an AR that contributed to extreme rainfall and severe flooding in the Southwestern Cape of South Africa in late September 2023. The heavy rainfall resulted in floods, landslides, and flood-damage that is still being rectified two years later. Atmospheric River events such as this one highlight the role ARs can have – one landfalling event can contribute significant amounts to monthly rainfall totals and can have severe effects on the local community. One of the key steps in bridging the knowledge gap in ARs is understanding the frequency, intensity and location of such features. There are various means to do this, but they all have the fundamental steps of identifying and tracking an AR. Figures 2 and 3 showcase how the late September 2023 AR in the South Atlantic is identified and tracked. Refining such methods on Atmospheric River observations is central to better understanding ARs in a modelled world – with climate models being an essential tool to better understand a changing climate.

What exactly the future holds remains uncertain, but a warming climate will allow for the atmosphere to hold more water vapour, which means ARs may become more intense. This could potentially contribute to heavier rainfall when they make landfall. Therefore, while Atmospheric Rivers could provide much-needed water during dry periods, they also carry the risk of producing more destructive floods in the years to come. Or ARs, even though more intense, could shift further poleward in a future climate, making infrequent landfall in South Africa, leading to severe drought conditions. These scenarios are of concern for regions already facing severe swings in rainfall variability and highlights some of the challenges associated with understanding AR impacts.

Despite spanning thousands of kilometres, Atmospheric Rivers are not as easy to represent in climate models as one might think. Their defining features – long, narrow, concentrated plumes of water vapour transport, and the location of their landfall, can all be sensitive to the resolution of the model used. In more coarse-resolution models, ARs can be poorly represented, which can make it challenging to develop robust storylines of the impact ARs may have in a warming climate.

Advances in computing power have allowed for the running of higher-resolution global climate models, such as those in Project EERIE. These models can better capture Atmospheric River characteristics and the complex interactions between the ocean and atmosphere that drive these features. For regions such as Southern Africa, where current models struggle to capture key systems that produce rainfall, this is highly beneficial. Higher-resolution simulations will allow us to better understand the role of features, such as the ocean mesoscale, have on the intensity and location of ARs. For Southern Africa, this will improve preparedness for both drought and flood risks, ensuring that these ‘rivers in the sky’ are better understood before they arrive on our doorstep.

[Want to learn more about ARs? You can watch Amber Sneddon presenting her work on Climatology of Atmospheric Rivers in the South Atlantic Basin using modern image processing-based methodology in our ‘Storms, Eddies and Science Hour’ online seminar below.]